Contents

Chapter 1 - Progress in reducing emissions

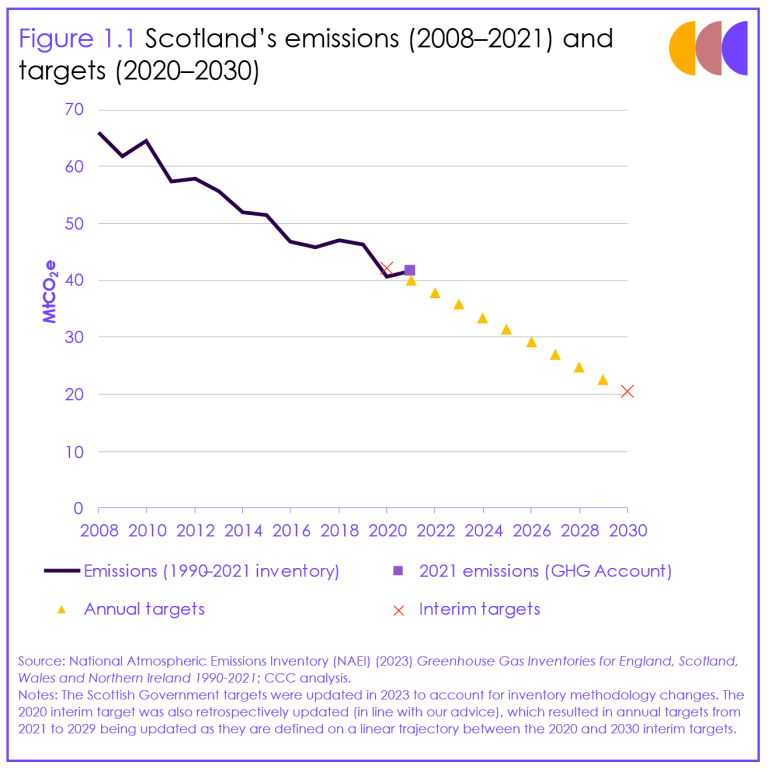

Scotland has a legislated target to reach Net Zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2045, with future interim targets in 2030 and 2040, as well as legal annual targets.

This chapter outlines Scotland’s progress towards these targets based on the latest available territorial emissions data, which cover the period up to 2021. We also present the most recent data on Scotland’s consumption emissions and monitor other indicators of delivery progress.

Our key messages are:

- Emissions in 2021 increased by 2.4% compared to 2020 levels, to 41.6 MtCO2e. The increase in 2021 was driven by an increase in surface transport emissions following the pandemic and an increase in buildings emissions, with colder than average temperatures contributing to the rise.

- Scotland narrowly missed its 2021 annual emissions reduction target of a 51.1% reduction in emissions compared to baseline levels.[*] Using the ‘base inventory’ methodology for GHG emissions, under which targets are assessed, emissions fell by 49.9%.

- Emissions reduction needs to accelerate in all sectors outside of electricity supply. The rate needs to increase by a factor of nine over the nine years from 2021 to 2030 compared to the preceding nine years, if Scotland is to meet its 2030 target (for emissions excluding electricity supply, aviation, and shipping). This is now beyond what is credible. There has been no recent progress in emissions reduction in the buildings, agriculture, land use and waste sectors.

- In 2019, Scotland’s consumption emissions fell by 1% to 76 MtCO2e, which is 64% higher than Scotland’s territorial emissions. Consumption emissions in 2019 were 24% lower than 1998 levels.

- Almost all key indicators of delivery progress are off track, with tree-planting and peatland restoration rates, heat pump installations, electric van sales and recycling rates significantly so. There has been better progress in renewable electricity generation, with offshore wind capacity ramping up significantly in 2022.

[*] Under Section 36 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, emissions reductions in future years will need to be steeper in order to outperform future targets to compensate for the excess emissions in years in which targets were missed.

1.1 Progress in reducing territorial emissions

1.1.1 Total emissions and the 2021 target

- Emissions in 2021: emissions were 41.6 MtCO2e in 2021, based on the 1990-2021 inventory. This is a 2.4% increase since 2020 but remains 10.0% below pre-pandemic levels in 2019. Emissions in 2021 were 49.2% lower than levels in 1990 (Figure 1.1). This represents a higher reduction in emissions compared to the UK, where 2021 emissions were 47.2% below 1990 levels.[1]

- Scotland’s 2021 target: using Scotland’s ‘base inventory’ methodology for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions accounting (Annex 2), under which the Scottish Government’s targets are assessed, emissions in 2021 were 49.9% lower than baseline levels.[*] Therefore, Scotland has narrowly missed its 2021 annual target of a 51.1% reduction on baseline levels (Figure 1.1). [**],[2],[3]

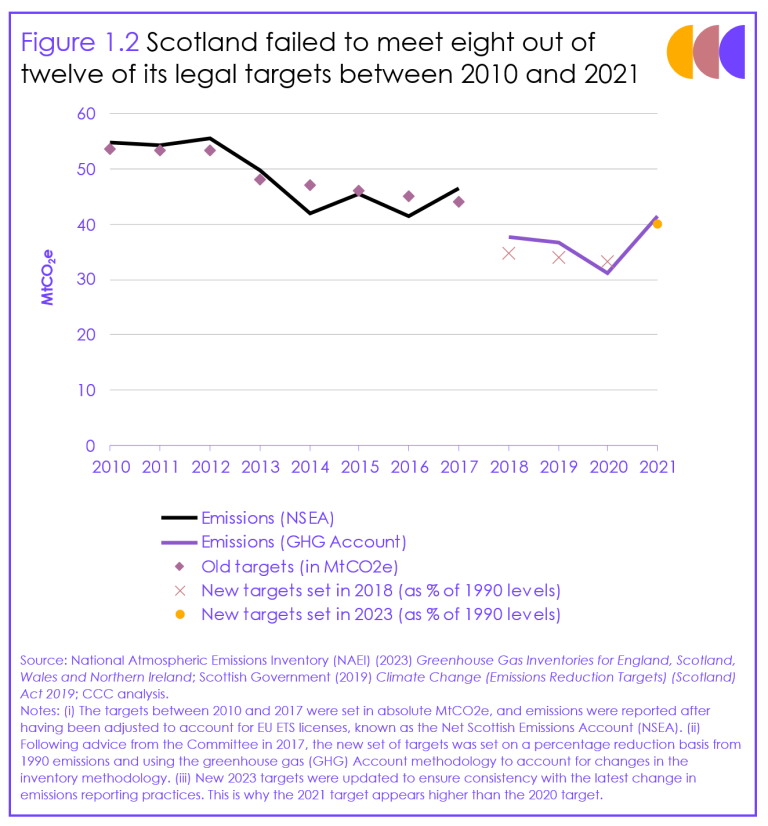

- Scotland’s previous targets: Scotland has failed to meet eight of its twelve legislated annual targets since 2010 and three out of four since 2018 (Figure 1.2). Stronger action is needed to reduce emissions across the economy to be able to meet future targets. Failure to meet future annual targets will increase the risks of Scotland missing its long-term emissions reduction goals.

[*] The baseline against which targets are assessed is 1990 emissions for all sectors except F-gases, for which 1995 is used.

[**] Following the CCC’s advice, the Scottish Government in 2023 updated its annual targets from 2020 onwards to account for the latest inventory methodology changes. Unless otherwise stated, this chapter refers to these targets. The 51.1% target was based on our recommendation to adjust annual targets in the 2020s to reflect changes in emissions accounting methodology.

1.1.2 Sectoral emissions

For consistency and to ensure comparability, this report categorises emissions by the sectors used in the Scottish Government’s 2020 Climate Change Plan update (CCPu).[4] The other chapters use CCC sectors. Annex 2 maps out the difference between the sectors used in this chapter and the CCC sectors.

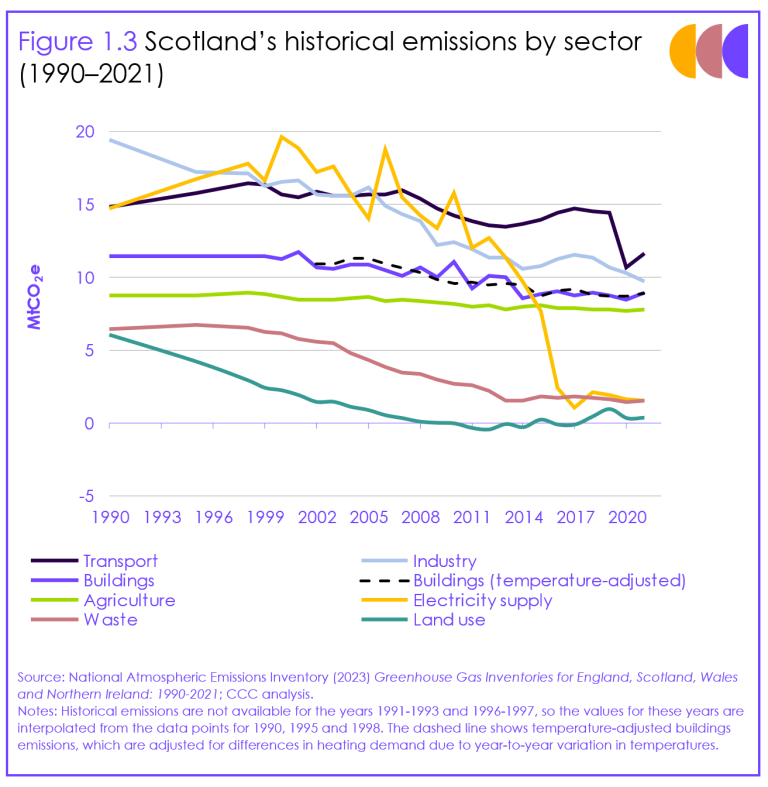

- Sectoral emissions changes in the last three decades: since 1990, the electricity supply sector has contributed the most to emissions reductions in Scotland, driven by the phase-out of coal and the growth of renewable energy (Figure 1.3). Significant reductions have also been seen in the industry, waste, and land use sectors. Emissions reductions in other sectors have been modest.

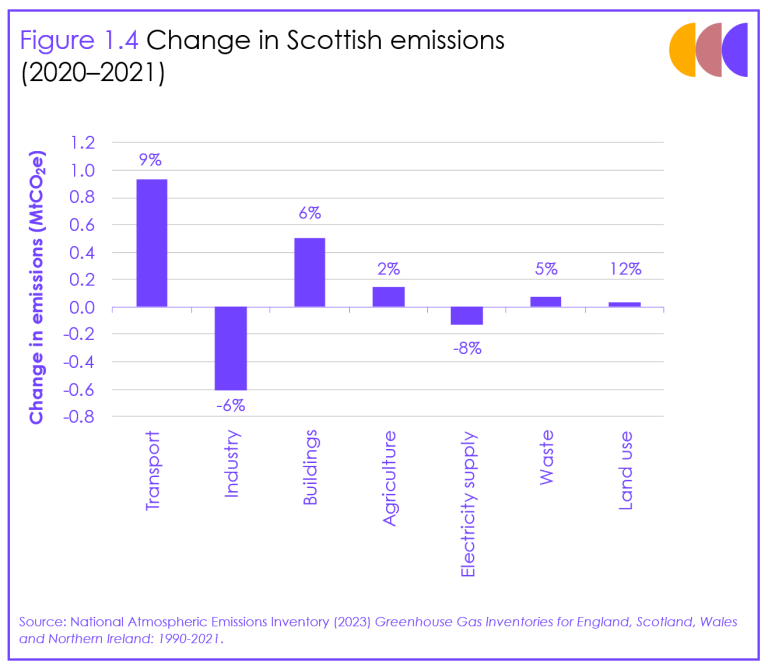

- Sectoral emissions from 2020 to 2021: changes in sectoral emissions from 2020 to 2021 are shown in Figure 1.4.

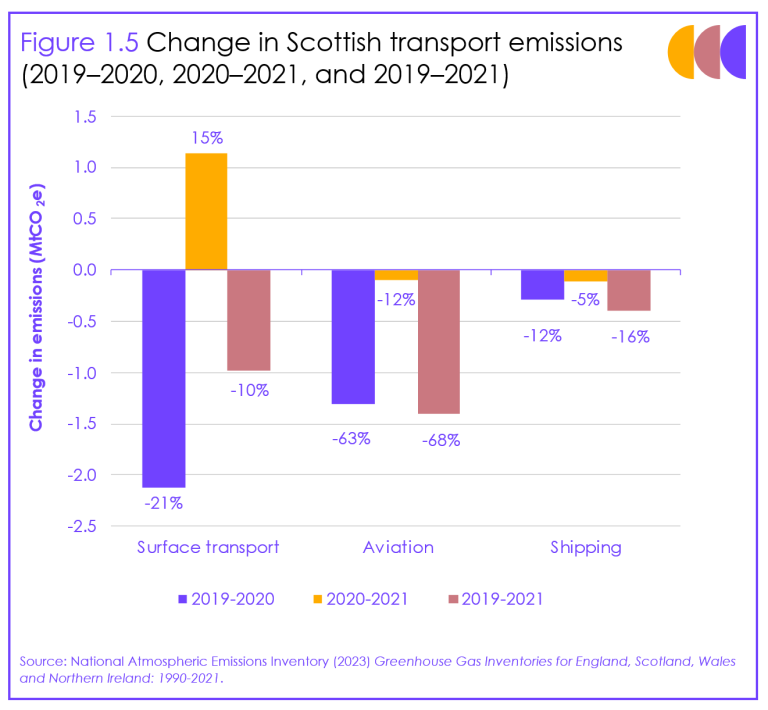

- Transport: emissions increased by 9% from 2020 to 2021 but remain 19% below pre-pandemic levels in 2019. This was driven by a 15% rise in surface transport emissions, which remain 10% below 2019 levels. Aviation and shipping emissions fell slightly and remain 68% and 16% below 2019 levels, respectively (Figure 1.5).

- Buildings: emissions increased by 6% from 2020 to 2021, with colder than average temperatures contributing to the rise.

- Industry: emissions decreased by 6% in 2021 compared to 2020 levels, driven by a reduction in fuel supply emissions from petroleum refining and oil and gas extraction, likely due to extensive periods of maintenance (both planned and unplanned).

- Electricity supply: emissions fell by 8% in 2021 due to a reduction in gas-fired generation. Electricity generation from gas in Scotland fell by 0.7 TWh (13%) in 2021.

- Agriculture, land use and waste: emissions all increased from 2020 to 2021. There has been no progress in reducing emissions in these sectors in the last eight years.

1.1.3 Required pace of future emissions reduction

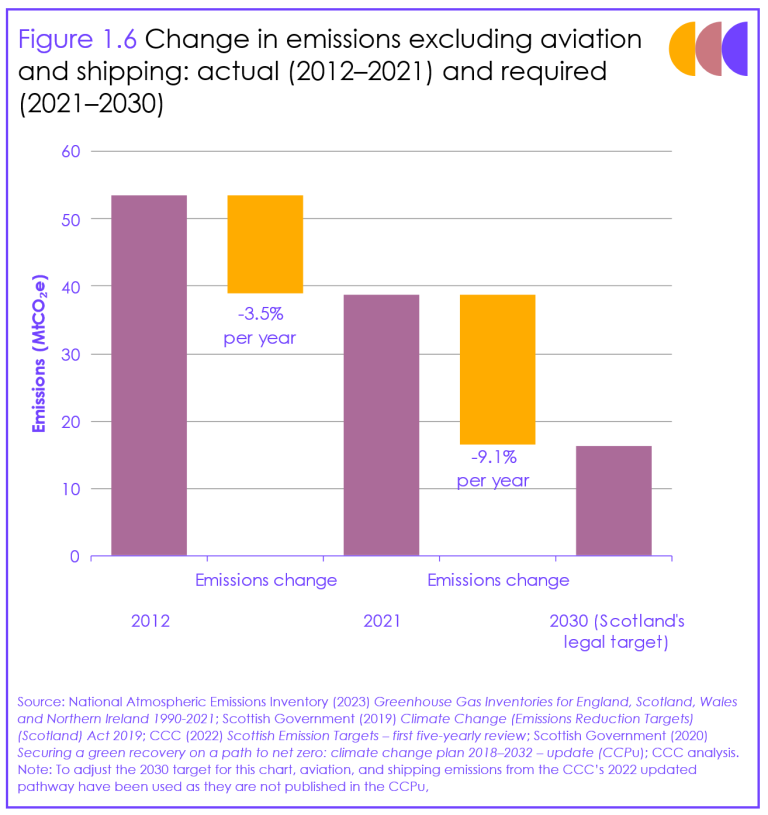

The rate of emissions reduction will need to accelerate rapidly for Scotland to meet its 2030 interim target of a 75% reduction in emissions compared to 1990 levels.[*]

- Excluding emissions from aviation and shipping, which were significantly affected by the pandemic, emissions in 2021 have fallen by 14.7 MtCO2e in the nine years prior to this (since 2012). This corresponds to a reduction of 3.5% per year on average. This will need to accelerate to an average of 9.1% per year for Scotland to achieve its 2030 target (Figure 1.6).

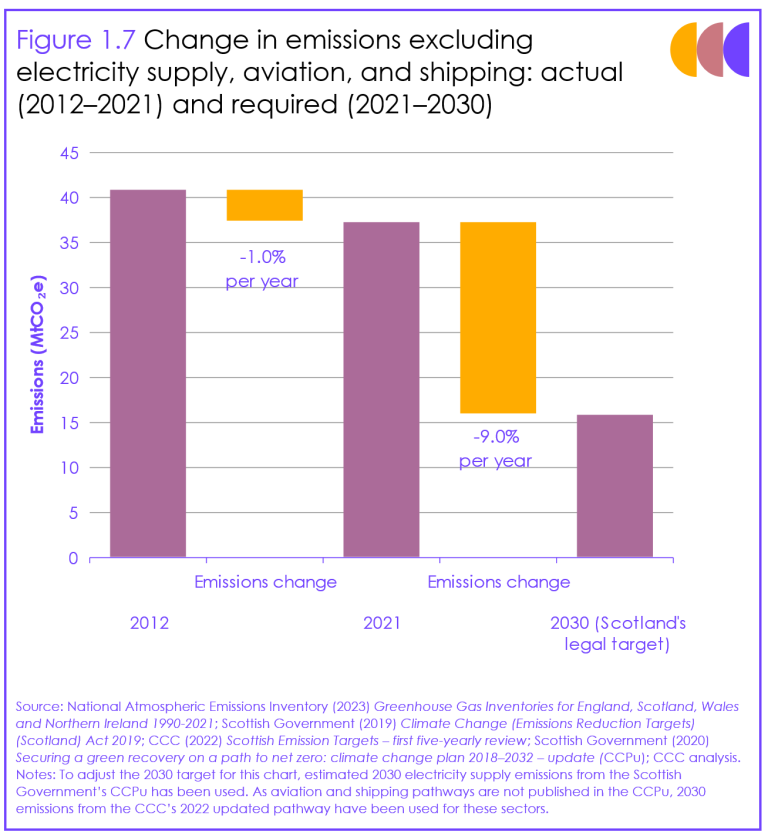

- If emissions from electricity supply, which have driven the bulk of reductions over this period and have limited potential for further reduction (Figure 1.7), are also excluded, emissions in the last nine years fell by only 3.6 MtCO2e, corresponding to an average annual reduction of 1.0%. This will need to increase by a factor of nine[**], to an average annual reduction of 9.0%, for Scotland to achieve its 2030 target (Figure 1.7). This would require annual emissions reductions almost twice as fast as those assumed over this period in the ambitious updated pathway for Scotland set out in the CCC’s 2022 advice on Scottish Emissions Targets.[***] Given the pace at which supply chains and investment would need to develop, this rate of reduction is not credible.

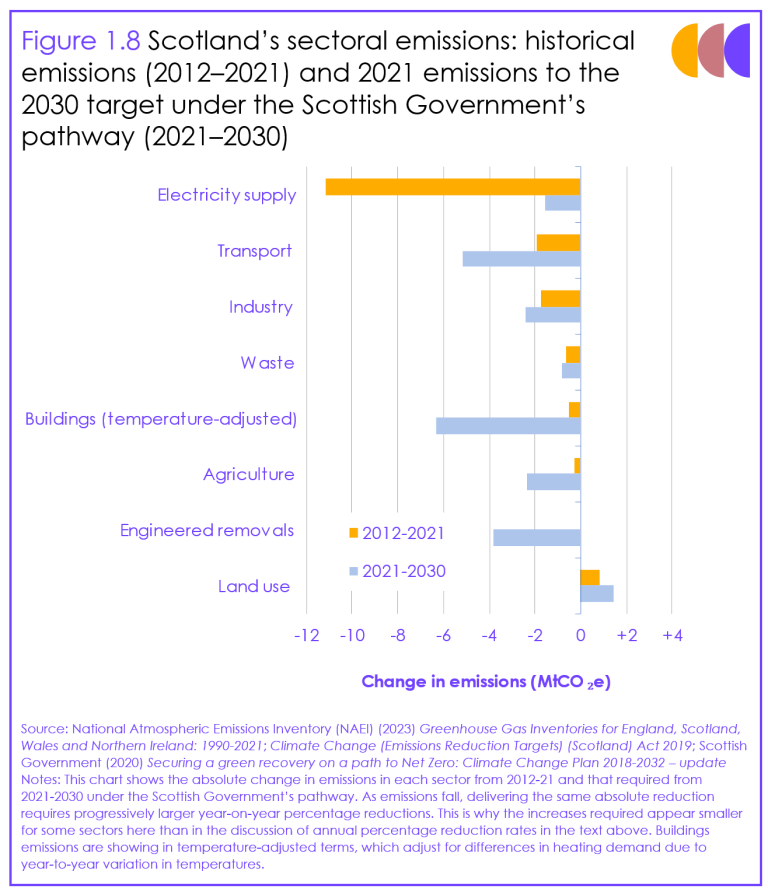

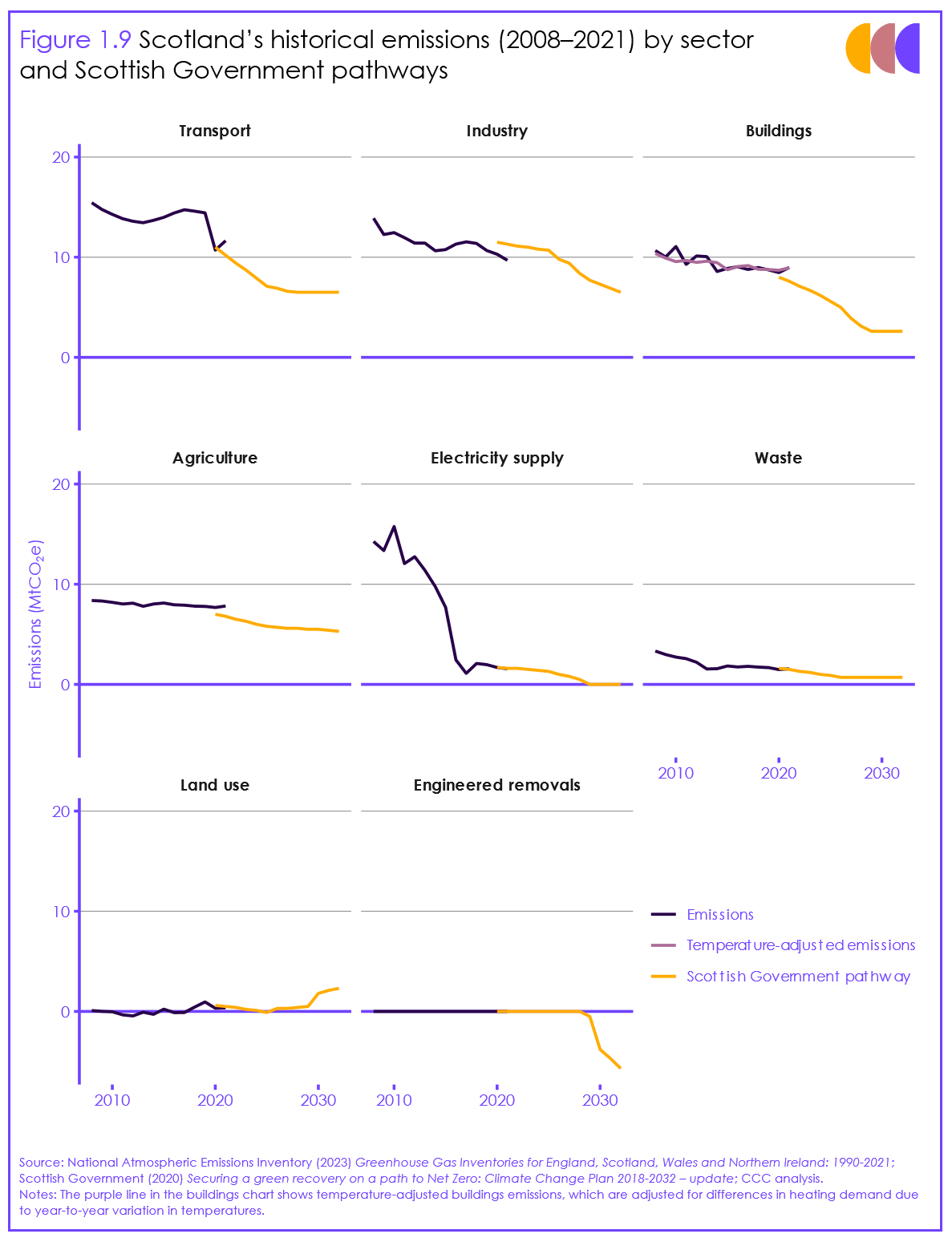

Emissions reductions will need to accelerate in all sectors apart from electricity supply, with a particularly rapid increase required in the buildings and transport sectors due to the ambitious decarbonisation pathways in those sectors in the Scottish Government’s CCPu. Engineered removals will also need to be rapidly deployed and ramped up significantly (Figure 1.8 and Figure 1.9).

- The yearly percentage change in emissions reduction needed in the buildings sector in the nine years from 2021 to 2030 according to the CCPu is almost a factor of ten higher than the reductions seen over the previous nine years. This required pace of reduction is almost three times that in the CCC’s ambitious 2022 updated pathway.

- The Heat in Buildings consultation has potential to accelerate buildings decarbonisation, but its effective and prompt implementation is crucial to achieve the required steep emissions reductions.

- The annual rate of reduction in transport emissions will need to be almost four times higher from 2021 to 2030 than it was from 2012 to 2021 to meet the sector’s contribution to the CCPu.[****] While a scale-up in this sector is expected as EV sales rise and measures are implemented to manage car and aviation demand, this pace would need to be almost twice as fast as in the CCC’s 2022 ambitious updated pathway.

- The rate of emissions reduction in agriculture will also need to ramp-up significantly to meet the CCPu pathway.

- The CCPu aims to achieve -3.8 MtCO2 of engineered removals annually by 2030. As this is currently zero, it will require a rapid initial deployment and ramp-up to be achieved. A feasibility study published by the Scottish Government estimates potential for only -2.2 MtCO2 by 2030 in Scotland.[5]

Our assessment on the credibility of the 2030 target is based on our sectoral assessment of policies and delivery indicators, and these comparisons showing how the decarbonisation rate required in the next nine years compares against that achieved over the preceding nine years and to the CCC’s ambitious 2022 updated pathway for Scotland.

[*] This target will be assessed against the GHG account for 2030.

[**] This factor of nine increase represents the increase in the average annual percentage reduction in emissions that will be required over 2021-2030, compared to that achieved over 2012-2021. These annual percentage reductions are calculated as the compound average rate at which emissions have fallen, or need to fall, over the relevant period.

[***] This updated pathway includes a range of possible engineered removals in Scotland on the basis of the Acorn cluster receiving track 2 status and goes further in ambition than our Balanced Pathway by implementing measures from our highly ambitious Tailwinds scenario in areas of the transport, buildings, agriculture, land use and waste sectors that have sufficient devolved powers. This results in an ambitious pathway that achieves 65-67% emissions reduction by 2030 and 91-101% by 2040, relative to 1990 levels.

[****] As emissions fall, delivering the same absolute reduction requires progressively larger year-on-year percentage reductions. This is why the increases required shown in Figure 1.8, which are shown in absolute terms, appear smaller for some sectors than those discussed here, which consider annual percentage reduction rates.

1.2 Progress in reducing Scotland's consumptions emissions

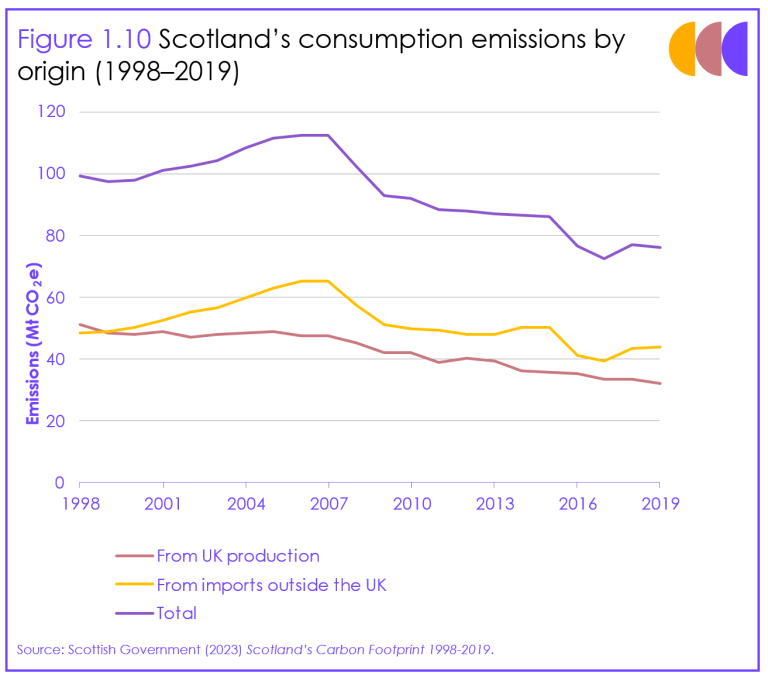

In this section we report on Scotland’s progress in reducing consumption emissions, which measure emissions arising from Scottish consumption, regardless of where they occur globally.

- Scotland’s consumption emissions fell by 1% to 76 MtCO2e in 2019, which is 64% higher than Scotland’s 2019 territorial emissions (46 MtCO2e).[*] Consumption emissions in 2019 were 24% lower than 1998 levels (Figure 1.10).

- Compared to 1998, Scotland’s emissions from imports from outside the UK and from UK production in 2019 respectively fell by 9% and 37%. As a result, the share of Scotland’s consumption emissions coming from imports from outside the UK, as a portion of total consumption emissions, has gradually increased over time.

- On a per-capita basis, Scotland’s consumption emissions in 2019 were 14 tCO2e per person, which is higher than the UK’s 10 tCO2e per-capita equivalent. This reflects the fact that both territorial and imported per-capita emissions are higher in Scotland than for the UK as a whole.

[*] Due to their uncertainty, emissions from land use, land use change and forestry are not included in the consumption emissions data reported by Scotland or the UK. The CCC has recommended that the UK Government invests in improving data availability in this area, building on the progress made by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

1.3 Sectoral indicators of progress

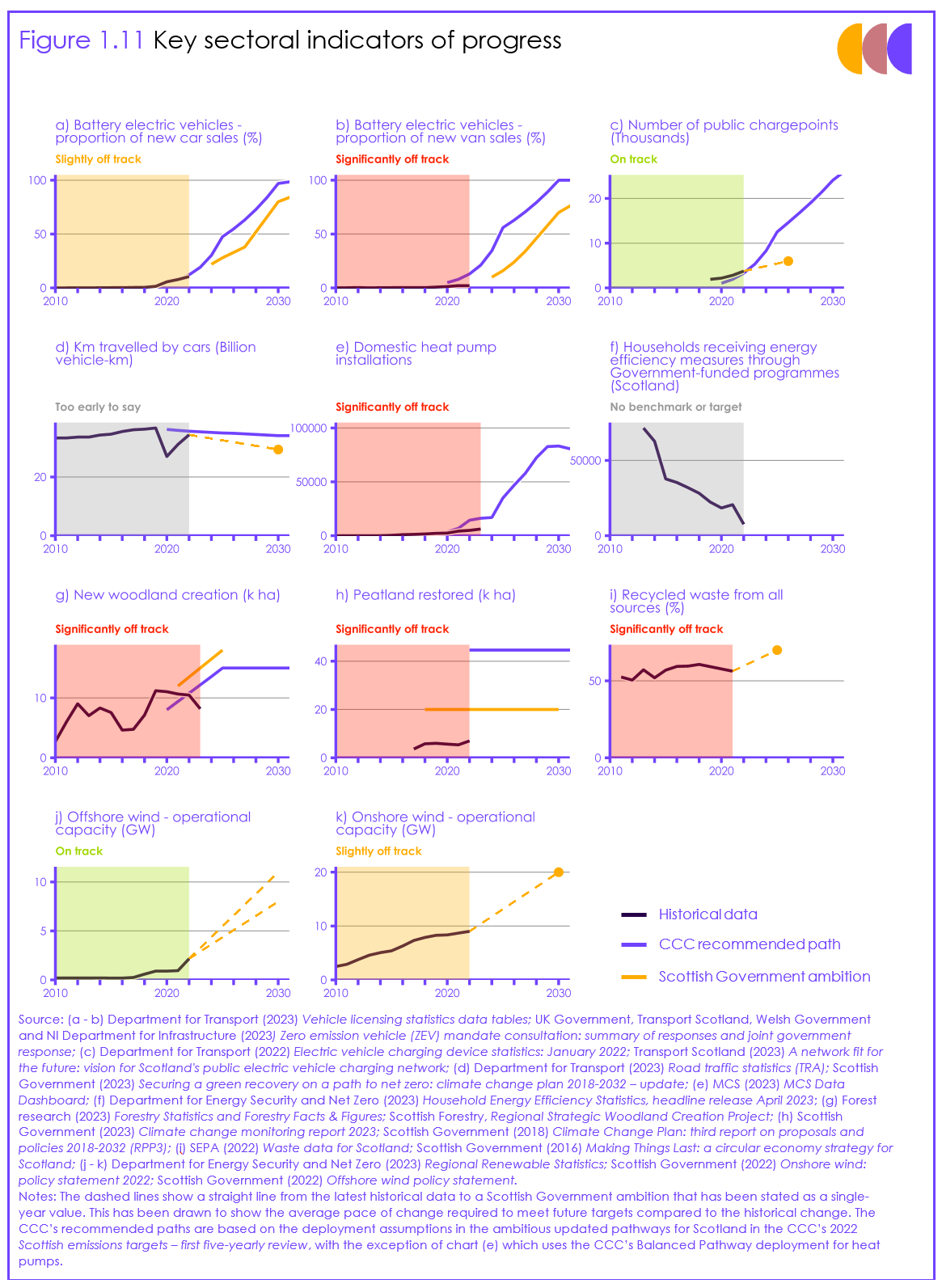

Figure 1.11 shows some key indicators of sectors’ progress in Scotland. With the exception of electric vehicle charge points and offshore wind capacity, all indicators are either significantly or slightly off track to meet Scotland’s own targets, or it is too early to make a judgement. Delivery needs to accelerate extremely rapidly if the factor nine increase in the rate of emissions reduction required for the 2030 target outside the electricity supply, aviation and shipping sectors is to be achieved (Figure 1.7).

- Battery electric vehicles and charge points: The share of battery electric car and van sales are respectively slightly and significantly off track, while the provision of public charge points is on track. Sales of battery electric vehicles and public charge point installations will both need to ramp-up to meet future targets.

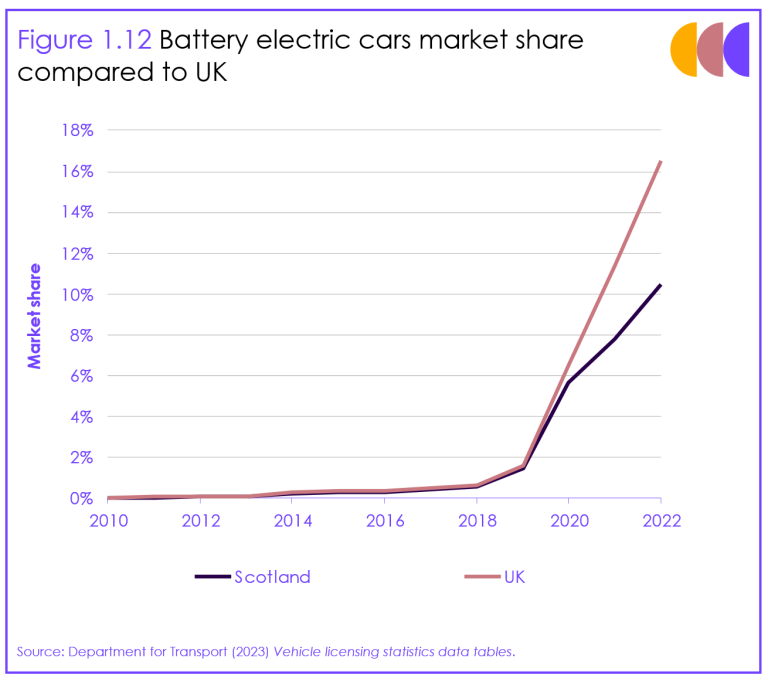

- In 2022, 10.5% of new car sales were battery electric, which is lower than both the CCC pathway of just over 12.2% (Figure 1.11a) and the UK whose share was 16.6% (Figure 1.12).

- As only 2.0% of new vans sold were battery electric in 2022, Scotland is significantly off track and sales need to accelerate rapidly to exceed the zero-emission vehicle mandate’s 16% target in 2025 (Figure 1.11b).

- There were around 3,800 public charge points in 2022 (Figure 1.11c). As such, Scotland is on track compared to the CCC pathway of 3,300 in 2022. Yet, public charge point provision will need to increase rapidly to deliver Scotland’s proportional share of required UK charging infrastructure. This is around 24,000 by 2030, which will require average annual deployment rates across the rest of the decade to be nearly three times current 2022 installation rates. Reliability must also improve.

- Reduction in car-km: in 2022, total kilometres travelled by car bounced almost fully back after the fall due to pandemic restrictions, with levels only 6% lower than in 2019 (Figure 1.11d). This is a slightly larger rebound than in the UK, where car-kilometres in 2022 were 7% lower than in 2019.

- Scotland has a highly ambitious target to achieve a 20% reduction of car-kilometres by 2030, against a 2019 baseline, but it is too early to say whether it is on track to achieve it due to the impact of the pandemic.

- There is currently a lack of clear policies to achieve this ambitious target. A delivery plan is needed to consolidate the post-pandemic reductions in car demand and introduce further incentives to switch journeys to more sustainable modes.

- Domestic heat pump installations. In 2023, just over 6,000 heat pumps were installed in Scotland, which is less than half of the installations in the CCC’s pathway (Figure 1.11e). According to the CCPu, meeting Scotland’s 2030 emissions reduction target requires heating system conversions of between 5% and 10% of homes, which equates to over 100,000 homes per year.[6] Action needs to ramp-up significantly and rapidly if Scotland is to meet its future targets.

- Energy efficiency measures: the number of Scottish households receiving energy efficiency measures through government-funded programmes has fallen over time, with the peak reached in 2013 when more than 71,000 households received such measures, down to 7,600 in 2022 (Figure 1.11f).

- The fall was driven by a fall in measures delivered through the UK Government’s Energy Company Obligation fund (ECO) since 2014. England, Scotland, and Wales all experienced a similar decline in the number of measures delivered through ECO over this period.

- The fall in measures delivered through ECO is down to a variety of reasons, including reduced funding from 2013, eligibility restrictions, and structural features of the scheme.

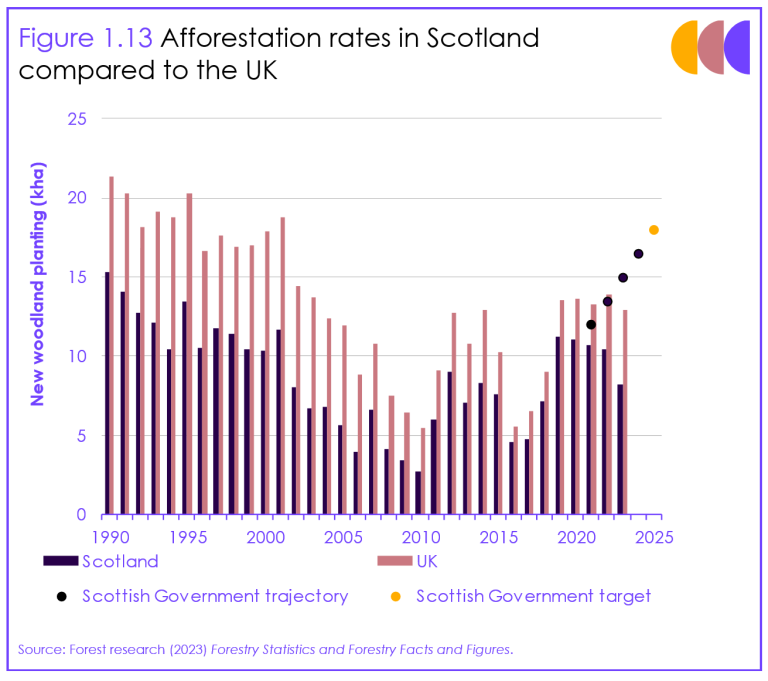

- Woodland: Scotland’s planting rates currently exceed those of the other UK nations combined, having planted about 63% of UK’s new woodland between 2022 and 2023 (Figure 1.13).

- However, since 2019 there has been a decreasing trend, and in 2022/23, Scotland planted just over 8,000 hectares (ha) of new woodland, which is a decrease from the previous year

(Figure 1.11g). - As such, the Scottish Government objective of 15,000 ha has been missed and Scotland is significantly off track to meet its target of 18,000 ha per year from 2024 to 2025, which would require current planting rates to more than double. The Scottish Government has stated that it expects to deliver only 9,000 ha per year following recent funding cuts.

- However, since 2019 there has been a decreasing trend, and in 2022/23, Scotland planted just over 8,000 hectares (ha) of new woodland, which is a decrease from the previous year

- Peatland: Scotland has missed its peatland restoration target for the fifth year in a row, with 7,000 ha of peatland restored in 2022/23 (Figure 1.11h). Restoration rates have almost doubled over the last six years, but the rate needs to nearly triple if Scotland is to meet its target of 20,000 ha per year, which in turn is less than half of the CCC’s recommended rate.

- Waste recycling.There has been no significant progress on the proportion of waste recycled or composted in Scotland, with levels fluctuating between 51% and 61% since 2011 (Figure 1.11i). Scotland is significantly off track to meet its ambition to recycle or compost 70% of all waste by 2025.

- Onshore and offshore wind: progress is on track to deliver on ambition for a total of 8-11 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030 (Figure 1.11j). However, Scotland is slightly off track for its ambition to deliver 20 GW of onshore wind capacity by 2030 (Figure 1.11k).

- Operational capacity of offshore wind increased by 1.2 GW in 2022, more than doubling total capacity to 2.2 GW. An average annual deployment rate of 0.7-1.1 GW is now required to deliver the 8-11 GW ambition of offshore wind by 2030.

- The growth of onshore wind in Scotland has slowed in recent years and only 0.3 GW was deployed in 2022.[*] To meet its 2030 ambition, Scotland must increase the deployment rate of onshore wind by more than a factor of four to an average annual rate of 1.4 GW.

[*] This refers to the capacity of onshore wind newly deployed in 2022, rather than to cumulative levels.